The news of the MACBA ‘scandal’ in Barcelona about the sculpture of Ines Doujak arrived with less resonance to Vienna. Not so in our collective (of people marked by the Latin American migratory experience) where the uneasiness was immediate: Ines Doujak, an Austrian artist that travels to Andean countries since 1978 and collects Andean textiles because “they speak and have stories to talk about”. In 2009 she obtains a prize for around 350,000 Euros from the Austrian State to produce an “art-based research” in Bolivia. (http://bit.ly/1G7Bizb). ‘Items brought from the Andean region to Europe are posted out to responders and have often stayed abroad for months’. Artists, poets, philosophers are invited to write about them (http://bit.ly/1Bh9eNX).The result of the work is collected in the Eccentric Archive which is addressed to a English-speaking audience. http://www.inesdoujak.net/eccentric-archive/

THE SCULPTURE

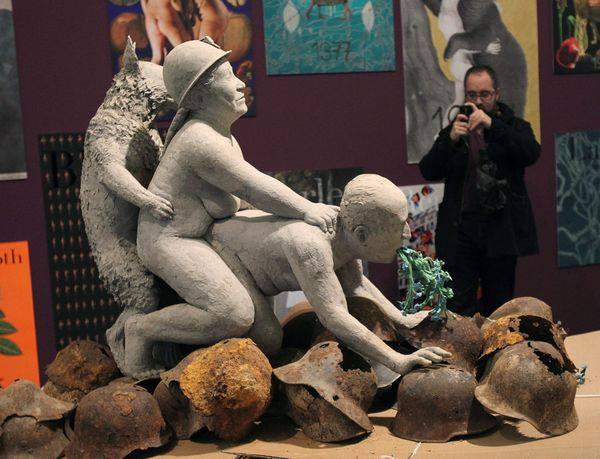

Photo description: White sculpture of a German shepherd penetrating a naked Domitila Barrios who wears a miners helmet and penetrates with a complacent smile the (ex)King Juan Carlos of Spain, who vomits flowers on top of SS helmets.

Loomshuttles/Warpaths http://bit.ly/1epDuMO is the main title of the ongoing project addressing textiles http://bit.ly/1RbHYT6. The piece ‘Not Dressed for Conquering. Haute Couture 4. Transport’ is made in collaboration with the English artist John Barker and exhibited in the 2014 São Paulo Art Biennial. ‘Haute Couture’ is french for High Dressmaking. ‘Not Dressed for Conquering’ is ‘the response beggars in 1619 Lima gave to the Spanish invaders’ demand that they should work instead of asking for money.’ (http://bit.ly/1IfjmEo).

INDIGNATION AGAINST CENSORSHIP

An artwork that claims itself as a critique to colonial relations and the dominion of Europe towards Latin America, and says to ‘subvert relations of power’ puts an indigenous woman to anally penetrate the king of Spain and to be penetrated by a dog on top of nazi helmets and packaging cardboards. Ines Doujak in “Haute Couture 4. Transport” makes a literal reproduction of ‘The Beast and the Sovereign’ lecture by Derrida. The sculpture scandalizes the MACBA’s director whose concern is not to offend the royal family. The curators are unwilling to remove the work and write a manifesto against censorship: “the work inscribed itself within the tradition of parody, carnival sculptures and iconoclast caricatures. The work was not meant to insult a private person, but to reformulate critically a collective representation of sovereign power. The curator Valentin Roma says “The rejected sculpture is part of a project initiated in 2010 that brings light about the asymmetric and complex relations between Europe and Latin America. It is a work that is inscribed in the great tradition of relations between art and power. Art has been caricaturing the archetypes of power for centuries, which is what Doujak’s work is doing. This is why in an exhibition about rethinking sovereignty nowadays we couldn’t accept to remove it. Probably many would have not realized who is the character because this is not what is important in the work”. The director cancels the exhibition and after the media coverage of the artists community reaction in Barcelona, he is fired by the board of trustees, as so are the curators by request of the salient director. After days of manifests, think pieces, articles and protests, the collective exhibition with the work of the thirty international artists finally opens with a reported 48 percent increase in visitor numbers, according to El País. http://bit.ly/1H0gWig

¿WHAT IS DOMITILA DOING THERE?

Dozen of pages are written about all the actors and subjects involved: about Not Dressed to Conquer/ Haute Couture 4. Transport, about the Spanish curators Paul Preciado and Valentin Roma, and the German co-curators Hans D. Christ and Iris Dressler, about the artists, the director, the King, the Queen as a sponsor of the museum, the Macba and their contract with the Wurttemberg Kunstverein. And of all these people not a single person questions if a helmeted, naked Domitila trapped between a dog and the king of Spain is really a critique of colonialism. The only statement by Doujak that is cited is the one she gives last December in the São Paulo Biennial, about how the work “plays with power relations and subverts them.”

In the center of all gazes, in the very middle of an artwork that supposedly criticizes colonialism, Domitila and what she represents remains invisible to all. Here in the most mediatic moment a political artist concerned with oppression could wish for, Ines Doujak says nothing. Neither do the curators. Nobody speaks up or seems to be bothered by the objectualization of Domitila. The whole perspective that would make her struggle as a political subject to be understood is missing.

The paradoxical aspect of this is that Domitila Barrios became famous precisely because she made her voice be heard in the most adverse circumstances. Even when imprisoned and pregnant, she survives a physical assault and a violent rape attempt by the police that seeks to traumatize her activism. This as a part of systematic measures in Latin America that silence and kill indigenous populations that protest against neoliberal measures. Domitila, returning kicks and spits, makes herself heard and never renounces to the capability of her own agency.

Knowing this history makes to show her in this situation more violent. ¿How can a work be anticolonial when it depicts a person as if it was a papier maché doll? If it supposedly wants to comment on the exploitation of indigenous bodies on the hands of the Spanish crown, ¿in whose imagination sexual violence is reverted when it is returned by the same means to the aggressor? ¿Why would anal sex would be an emancipatory dispositive for a region whose pre-columbian imaginary is populated by representations and sculptures of diverse sexual practices that include anal sex? ¿Why to weave her theoretically with Derrida when his references in this lecture (Homer, Aristotle, La Fontaine, etc.) http://bit.ly/1GGYDwx are centered in Europe? And finally, are the nazi helmets a comment to the invention of the concentration camp format by the Spanish crown in the territory of the current Cuba? Is Domitila then represented here as a generic sign of the indigenous without differencing the Caribbean history and the Andean history?

The violence towards indigenous women and the racialization and animalization of their bodies is a colonial inheritance and is not by any means a thing of the past. The sculpture of Doujak chooses to ignore this. It ignores the abundant colonial imagery and ‘scientific’ racist knowledge that was produced with the purpose to prove the underdevelopment and the primitivism of indigenous people.

Here we are exactly two months after the scandal and nobody of those involved have said anything about the whole strategy of the work and the failure of its conception and reception.

Not to forget that at play is also the relations between the north and the south of Europe. Producing a similar sculpture that was to comment on the colonial dominion of Austria, by making a worker rights female figure from Eastern Europe to anally penetrate the president of Austria would undoubtedly also produce an scandal that would have a different impact for Ines Doujak. This most likely would be prompted by a conservative reaction in certain political parties who are behind which budgets are intended for what cultural production or on the other end by understanding that the work is problematic.

WHO CAN CROSS THE ATLANTIC TO COLLECT ANDEAN TEXTILES?

It is necessary to reflect who speaks about whom and with what ultimate objectives. This precisely because there is a long colonial tradition of West Europeans making journeys to and through South America, to collect materials and information that become a production of scientific and academic works http://bit.ly/1BpmQqt. In this case the Bolivian textiles and other indigenous cultural goods are used as a point of departure for an interpretation work to be issued by experts outside the continent, rendering academic profits in which the original producers never take part.

The violence exercised here consists of going to the place of the Other, the subaltern and produce a sense of reality under a lense that is not addressed to initiate a dialog with the Other, but to explain the Other’s reality (http://bit.ly/1H0xWoD p.67) to an hegemonic audience. It is a oneway historical relation. The Other does not have structures and institutions that would back up a parallel reversion.

According to Gloria Anzaldúa. “the difference between appropriation and proliferation is that the first steals and harms, and the second helps to heal the breaches of knowledge.”

Domitila Barrios herself addressed the problematic of the appropriation of their struggle in her biography “Si me permite hablar..” (a reading we recommend: http://bit.ly/1xlKZfV) and says of those who come to talk about them: “Of all those materials that they take, there are very few which return (..) I would like to ask all these people who thinks they want to collaborate with us, that all the material that they took, that they return it to us (..) so that it is useful for the study of our own reality (..) I think that the films, documents, studies that are made about the reality of the Bolivian people must return to the Bolivian people so that they can analyze it and criticize it.”

Domitila Barrios herself addressed the problematic of the appropriation of their struggle in her biography “Si me permite hablar..” (a reading we recommend: http://bit.ly/1xlKZfV) and says of those who come to talk about them: “Of all those materials that they take, there are very few which return (..) I would like to ask all these people who thinks they want to collaborate with us, that all the material that they took, that they return it to us (..) so that it is useful for the study of our own reality (..) I think that the films, documents, studies that are made about the reality of the Bolivian people must return to the Bolivian people so that they can analyze it and criticize it.”

“Finally I want to make clear that the narration of my personal experience and of the experience of my people that is fighting for its liberation —and to which I am indebted—, I want that it reaches the poorest people, those who don’t have money, but need an orientation and an example for their future life. Because of them I accept that what I narrate is written. It doesn’t matter with which kind of paper but I want that is of use for the working class and not only for the intellectual people of for people who only profit with these things.”—p.9. (Our translation).

When we speak of one way we are talking about concrete issues such as the free transit in the world and whose passports are allowed to travel and have an experience of other cultures. In 1978 Doujak collects her first textiles in a trip to South America. In the same decade, three years before, Domitila Barrios is denied the possibility to leave Bolivia in order to attend a symposium she has been invited to in Mexico. Only with the support of her party she is able to fly to the event of which her interpellation to Betty Friedan were to become famous for problematizing the differences between the struggles of women of color in the ‘third world’.

When we speak of one way we are talking about concrete issues such as the free transit in the world and whose passports are allowed to travel and have an experience of other cultures. In 1978 Doujak collects her first textiles in a trip to South America. In the same decade, three years before, Domitila Barrios is denied the possibility to leave Bolivia in order to attend a symposium she has been invited to in Mexico. Only with the support of her party she is able to fly to the event of which her interpellation to Betty Friedan were to become famous for problematizing the differences between the struggles of women of color in the ‘third world’.

For those of us who are marked by the experience of Latin American migration (Andean, Caribbean, etc.) in Europe and work from the arts and activism as a way to heal the wounds of colonialism –its manifestation in our daily lives and its transgenerational actualization both on the level of individual practices and institutional measures– is urgent that West European artists question the normalization of the structures that are behind the mechanisms that sustain their privileges and their role in the reproduction of this oppression. In this line, is urgent a research on the colonial relations between Austria and Spain at the moment of the Conquest/Invasion and the capital accumulation that the blood ties between both crowns implied, as it is also urgent to understand how and why it is declared that some can travel while others are denied this possibility.

We are here, producing, dialoguing, and surviving on the way. We wish and need for an artistic production and a production of knowledges from the histories from where we come, in order to connect them with the new meanings we produce here and weave them with the imaginaires we have of the society in which we want to live.